Monday, August 28, 2006

Friday, August 25, 2006

Back from Vacation

Thursday, August 03, 2006

Investing in Complementary Innovation

- What complements are currently constraining demand in our core markets?

- What new product might boost demand for our core offerings?

- Would our customers buy more if they had better information?

- Would we learn valuable lessons by innovating in complements?

- Do we have competitors whose fortunes are tightly tied to the price of complements?

Monday, July 31, 2006

Innovation at Coke

- She's a Coke "lifer", which shows that Outside Intervention isn't always required to uncork innovative thinking.

- Her mission is to make "Coke more exciting, innovative, and relevant" (emphasis mine)

- She told her team to "stop thinking in terms of existing drink categories and start thinking broadly about why people consume beverages in the first place".

- "Like Henry Ford said, 'If I'd asked the consumer what they wanted, they'd have said a faster horse,' she told her troops. (In other words, lead your customer, as I mentioned in an earlier post.)

- She engaged bottlers (her channel) to gain their insights and cooperation in introducing new products.

- She's shaking up the culture at Coke and setting a higher standard. What had passed for innovation in the past "had been incremental line extensions that too often didn't really move the needle".

- While in charge of Coke's Japanese operations, she introduced over 100 new products a year, some with very short product lifecycles (months). Sounds like she's bringing some "Long Tail" thinking to Coke.

- Here are her four key items from the "PLAYBOOK: Best Practice Ideas" sidebar in the article:

- Anticipate the Customer

- Retool Tired Brands

- Engage Partners

- Don't Fear Failure

Thursday, July 27, 2006

If I Ran AOL...

...I'd be a very happy guy.

Here's what's going on in a nutshell (some more detail here). People have been signing up for broadband Internet access in droves, either cable or DSL. A few years ago, AOL had about 30 million subscribers, each paying about $20 a month for dial up access. AOL customers found themselves paying $40 a month for broadband AND $20 a month for AOL. They started asking themselves, "Why am I doing this?" and so many of them answered, "For no good reason" that AOL now has about 18 million subscribers.

For a while, AOL deluded itself by thinking it was a "content" company -- that the features that came with AOL were so special that they were worth charging a premium to get. They were wrong. The content is everywhere.

Now they think that they'll be an advertising company.

I think I have a better idea.

I'd make AOL a communications company. I'd use the Firefox browser and Thunderbird email programs (both of which AO

...I'd be a very happy guy.

Here's what's going on in a nutshell (some more detail here). People have been signing up for broadband Internet access in droves, either cable or DSL. A few years ago, AOL had about 30 million subscribers, each paying about $20 a month for dial up access. AOL customers found themselves paying $40 a month for broadband AND $20 a month for AOL. They started asking themselves, "Why am I doing this?" and so many of them answered, "For no good reason" that AOL now has about 18 million subscribers.

For a while, AOL deluded itself by thinking it was a "content" company -- that the features that came with AOL were so special that they were worth charging a premium to get. They were wrong. The content is everywhere.

Now they think that they'll be an advertising company.

I think I have a better idea.

I'd make AOL a communications company. I'd use the Firefox browser and Thunderbird email programs (both of which AO L owned lock, stock and barrel in earlier incarnations) in conjunction with AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) and an Internet phone/videophone program to form the core of my AOL service. I'd make them look and feel like the AOL mail that my customers have come to know, but add in more extensions and customization features. I'd integrate them into a single, interoperable platform with a common address book. I would develop this as an open source software platform that anyone could develop offerings for. This base would all be free of charge, and everyone who wanted an AOL.com email address could have one -- especially any of those 12 million people who've left.

For many of those 30 million subscribers, AOL was nothing more than an access company. That role is now taken by another part of TimeWarner, namely TWC, the cable business. So switch all access-related business to TWC -- including dial-up -- and charge reasonable rates for it. (For TWC's RoadRunner Internet cable subscribers, there is a travel feature that gives you dial-up access when you travel. In one of the only benefits of the AOL - TimeWarner merger, the dial up network that RoadRunner uses is the AOL network.)

Next, I'd recognize that I owned a LOT of servers. I'd use them to offer a lot of value-added services for my AOL people. Personal websites, online communities, photo storage and sharing. Hey, I might even have a Warner Brothers music and movie site with downloads! I'd form partnerships with other content and service providers to tap into the AOL network. These would carry modest fees.

I'd also think about developing AOL On-the-Go tablets (like the Nokia 770 Internet tablet) that offered seamless

L owned lock, stock and barrel in earlier incarnations) in conjunction with AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) and an Internet phone/videophone program to form the core of my AOL service. I'd make them look and feel like the AOL mail that my customers have come to know, but add in more extensions and customization features. I'd integrate them into a single, interoperable platform with a common address book. I would develop this as an open source software platform that anyone could develop offerings for. This base would all be free of charge, and everyone who wanted an AOL.com email address could have one -- especially any of those 12 million people who've left.

For many of those 30 million subscribers, AOL was nothing more than an access company. That role is now taken by another part of TimeWarner, namely TWC, the cable business. So switch all access-related business to TWC -- including dial-up -- and charge reasonable rates for it. (For TWC's RoadRunner Internet cable subscribers, there is a travel feature that gives you dial-up access when you travel. In one of the only benefits of the AOL - TimeWarner merger, the dial up network that RoadRunner uses is the AOL network.)

Next, I'd recognize that I owned a LOT of servers. I'd use them to offer a lot of value-added services for my AOL people. Personal websites, online communities, photo storage and sharing. Hey, I might even have a Warner Brothers music and movie site with downloads! I'd form partnerships with other content and service providers to tap into the AOL network. These would carry modest fees.

I'd also think about developing AOL On-the-Go tablets (like the Nokia 770 Internet tablet) that offered seamless  connectivity wherever I was. This could be a partnership with Nokia, or it could be an open source project that let people develop software and services around the platform. More partnership opportunities like this exist in the hardware space, as Apple has found with the iPod, iTunes Music Store, and the zillions of companies making iAccessories.

These partnership opportunities would position AOL at the crossroads of all Internet trends. AOL would be access-provider agnostic, which would benefit them greatly. They'd be an enabler of countless service opportunities for start-ups and established companies alike. It would be like creating a whole new, open ecosystem for Web 2.0. And AOL would be leading it rather than being a footnote to history.

What about advertising? I think advertising is a subsidy of a business rather than a business in and of itself. Most advertising is annoying and ineffective. I think that Google has done a very good job to rake in lots of money while maximizing the effectiveness and minimizing the intrusiveness of advertising. But Google is a search company, and they link the ads they serve to the content that you are looking for, dramatically improving relevance. My AOL would be a communications and services company, and (at this point), I can't see how advertising can reach Googlian levels of relevance. It would not be a key element in my business model.

P.S. This link to the parent of AOL (AOL LLC) shows that they already have many of the pieces. It's just a matter of deciding what they're in business to do, and executing.

connectivity wherever I was. This could be a partnership with Nokia, or it could be an open source project that let people develop software and services around the platform. More partnership opportunities like this exist in the hardware space, as Apple has found with the iPod, iTunes Music Store, and the zillions of companies making iAccessories.

These partnership opportunities would position AOL at the crossroads of all Internet trends. AOL would be access-provider agnostic, which would benefit them greatly. They'd be an enabler of countless service opportunities for start-ups and established companies alike. It would be like creating a whole new, open ecosystem for Web 2.0. And AOL would be leading it rather than being a footnote to history.

What about advertising? I think advertising is a subsidy of a business rather than a business in and of itself. Most advertising is annoying and ineffective. I think that Google has done a very good job to rake in lots of money while maximizing the effectiveness and minimizing the intrusiveness of advertising. But Google is a search company, and they link the ads they serve to the content that you are looking for, dramatically improving relevance. My AOL would be a communications and services company, and (at this point), I can't see how advertising can reach Googlian levels of relevance. It would not be a key element in my business model.

P.S. This link to the parent of AOL (AOL LLC) shows that they already have many of the pieces. It's just a matter of deciding what they're in business to do, and executing.

Monday, July 24, 2006

What is a strategy, and why do you need one?

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Market Research and Innovation

Monday, July 17, 2006

Introduction to Open Source Software

- Operating Systems (Linux and its many distributions, currently the most notable and usable of which is Ubuntu);

- Browsers (Firefox)

- E-mail (Thunderbird, these last two from the Mozilla Foundation)

- Office Suites (OpenOffice, almost fully compatible -- 99+% for most people -- with Microsoft Office)

Thursday, July 13, 2006

The Long Tail Starts Wagging

Monday, July 10, 2006

The Customer Buy Cycle

- Awareness,

- Consideration, and

- Conversion.

Thursday, July 06, 2006

Driven to Innovate

- It is a family-owned company, founded in 1934 and run by the third generation.

- They have over 600 employees, about 300 trucks and twice as many trailers, and revenues of about $50 million.

- They started out delivering movie reels to theaters. The only option up to that point was for theater owners to go to the rail station for pickup and delivery. A rail strike cemented their hold on the market -- when the strike was over, the theaters wanted to continue doing business with Benton.

- Deregulation of the trucking industry in the '80s opened the door for then to move into general commerce.

- Clete Cordero, VP of Business Improvement, said this in an interview on eTrucker.com: “You rarely see a trucking company go out of business because of lack of freight. It’s usually too much freight, too cheap.”

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

What can Small Businesses Learn from GM?

Thursday, June 29, 2006

Heinz Plays Catch-up

- Heinz had been a supplier to McDonald's until a tomato shortage in 1973, when Heinz made a decision to support its "glass bottle" customers instead of McDonalds. McDonald's was apparently none too happy, so they decided to end the relationship with Heinz, developed their own ketchup, and outsourced production.

- A company called Golden State Foods -- who started as a supplier to Ray Kroc (McDonald's founder) with a handshake deal -- currently is the dominant ketchup supplier to the restaurant company in the US. According to the article, "McDonald's sees no reason to switch."

- McDonald's uses 250 million pounds of ketchup per year in the US.

- A special seed business that creates "proprietary tomatoes"

- Heinz process for breeding that creates "better tasting tomatoes"

- A tracing system for its crops in the event of illness or tampering

- Different packaging to reduce the need to refill dispensers as often

- "A ketchup pot that attaches to a French fry cup that would make it easier for customers to dip fries while eating in cars."

- Innovation in the customer experience can differentiate your product.

- Once someone is established as a loyal supplier, it is very difficult to dislodge them.

Monday, June 26, 2006

Southwest Makes Hurricanes Work for Me!

Thursday, June 22, 2006

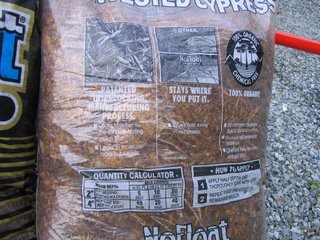

Innovation in Low Places (Low Tech, That Is)

The Corbitt Manufacturing Company of Lake City, Florida has figured it out, and has received a patent as well. The particular product we bought is called No-Float Mulch ("Stays Where You Put It"), and received US Patent 5,301,460.

The Corbitt Manufacturing Company of Lake City, Florida has figured it out, and has received a patent as well. The particular product we bought is called No-Float Mulch ("Stays Where You Put It"), and received US Patent 5,301,460.

One problem facing mulch customers was that the stuff would float and run off in heavy rains. H.C. Corbitt sought to rectify this, and developed a new process for "pulverizing wood product" and a new composition resulting from the process. (Briefly, there is a "shredded fine portion, a bulky portion, and a stringy binding portion", combined in a certain ratio.) The fact that it is made from cypress certainly helps (cypress doesn't tend to float as well as other woods).

No-Float costs a bit more than regular mulch, but it is probably a wise investment if it doesn't need to be replaced as often. And it certainly is an inspiration to the innovator in me!

One problem facing mulch customers was that the stuff would float and run off in heavy rains. H.C. Corbitt sought to rectify this, and developed a new process for "pulverizing wood product" and a new composition resulting from the process. (Briefly, there is a "shredded fine portion, a bulky portion, and a stringy binding portion", combined in a certain ratio.) The fact that it is made from cypress certainly helps (cypress doesn't tend to float as well as other woods).

No-Float costs a bit more than regular mulch, but it is probably a wise investment if it doesn't need to be replaced as often. And it certainly is an inspiration to the innovator in me!

Monday, June 19, 2006

A New Brand Model for Innovation

- Give cost advantages at the commodity level;

- Lift products and services out of the commodity level;

- Create new features and benefits for customers (and create new customers, too!); and

- Drive the development of a reputation that can become a source of competitive advantage -- a brand.

Monday, May 22, 2006

Innovation Gone Awry: #1, Where Less Would Have Been More

Wednesday, May 10, 2006

Core competencies: What are they and will they guarantee success if I have one?

At the same time, said Templeton, emerging markets such as India, China and Russia are adding billions of new consumers to the market "overnight," as those nations join the global economy.

This combination of more devices per consumer and more consumers overall will allow TI to continue to outgrow the semiconductor industry as it has for the past four years, said Templeton.

To me, this means that Dell's core competency in the PC market might not play as well in the emerging market dynamics of what's been called the "Post-PC Era". To summarize, there are two lessons about core competencies that I've learned throughout my practice and career: 1. Just being good at something doesn't a "core competency" make. 2. Core competencies aren't a guarantee of perpetual success.

Wednesday, May 03, 2006

iLove my iMac!

I am a switcher. A couple weeks ago, I bought one of the new Intel-based, dual core, 2.1GHz, Apple iMac, with a 20" diagonal screen. That's bigger than my first couple of TV sets, and whole lot nicer. That's it in the picture. That's the whole computer -- no other boxes. The CD/DVD slot drive is on the right edge (out of sight in this picture), and it will create both CDs an DVDs. It is running Mac OS X 10.4, also known as "Tiger".

Other than a version of Microsoft Office.X that I had for the other two Macs in the house (an iBook and a Mac Mini), I only needed to download Firefox. OK, "need" is a strong word, since Safari is a great browser, but I *like* Firefox.

An interesting thing about Microsoft Office.X -- this is the student and teacher edition, which is apparently available to anyone who is, was, teaches, or has, a student -- is that they let you install it on three different computers. Legally. This is totally unlike Office for Windows PC's, which allows you to install it on only one PC. This is the main reason I started looking at other operating systems -- alternatives to Windows. As I got more PC's in the house, the prospect of paying $400+ for legal versions of MS Office was ludicrous. So I found Open Source software, and the very good OpenOffice (which is free, almost totally compatible with MS Office, and available for Windows, Mac, and Linux), and thus started a four year tech journey that culminated with this purchase.

Back to the iMac...I tried Microsoft Entourage for email, but that was awful, so I switched to Apple Mail. Very nice, with some substantial usability improvements over the version in Panther (the previous OS X version before Tiger).

I've set up my Palm Tungsten T5 to sync with iCal and Address Book, and it does it wirelessly via Bluetooth, which is built in to both machines.

The point here is that everything you'd need to use a computer comes with this machine. Here's what you get with the machine:

I am a switcher. A couple weeks ago, I bought one of the new Intel-based, dual core, 2.1GHz, Apple iMac, with a 20" diagonal screen. That's bigger than my first couple of TV sets, and whole lot nicer. That's it in the picture. That's the whole computer -- no other boxes. The CD/DVD slot drive is on the right edge (out of sight in this picture), and it will create both CDs an DVDs. It is running Mac OS X 10.4, also known as "Tiger".

Other than a version of Microsoft Office.X that I had for the other two Macs in the house (an iBook and a Mac Mini), I only needed to download Firefox. OK, "need" is a strong word, since Safari is a great browser, but I *like* Firefox.

An interesting thing about Microsoft Office.X -- this is the student and teacher edition, which is apparently available to anyone who is, was, teaches, or has, a student -- is that they let you install it on three different computers. Legally. This is totally unlike Office for Windows PC's, which allows you to install it on only one PC. This is the main reason I started looking at other operating systems -- alternatives to Windows. As I got more PC's in the house, the prospect of paying $400+ for legal versions of MS Office was ludicrous. So I found Open Source software, and the very good OpenOffice (which is free, almost totally compatible with MS Office, and available for Windows, Mac, and Linux), and thus started a four year tech journey that culminated with this purchase.

Back to the iMac...I tried Microsoft Entourage for email, but that was awful, so I switched to Apple Mail. Very nice, with some substantial usability improvements over the version in Panther (the previous OS X version before Tiger).

I've set up my Palm Tungsten T5 to sync with iCal and Address Book, and it does it wirelessly via Bluetooth, which is built in to both machines.

The point here is that everything you'd need to use a computer comes with this machine. Here's what you get with the machine:

- iPhoto for digital photography;

- iTunes for music (of course);

- iCal for calendars;

- Mail for, well, mail;

- Safari for browsing;

- iChat for AIM compatible instant messaging (and video conferencing with the built in camara - the little black dot at the top center of the iMac in the picture);

- TextEdit for preparing documents (compatible with MS Word);

- and a ton of other little things, all nicely done.

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Book Recommendations: Strategy, and Linux

Article on Trade Secrets

Monday, April 10, 2006

Article: Do-It-Yourself Patents

- You can save a considerable sum of money. Most patent attorneys will charge in the $10,000 - $15,000 range to obtain a US patent. This will cover drafting the claims, writing the specification, handling the interaction with the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and paying the filing fees.

- You can directly control the content.

- You can perform prior art and freedom to operate searches by yourself, using the tools at the USPTO website, or other sites, like Free Patents Online. This can help you determine if your idea (or one close enough to it) has already been patented. If so, you can save yourself the time and expense of filing an application only to have it be rejected. These searches are not usually done for an ordinary filing by an attorney; you can request them for an additional fee.

- This is a time consuming process, and requires considerable attention to detail and deadlines. The USPTO has strict requirements about the format of drawings and claims, to name two.

- You should not only have excellent writing skills, but have a detailed understanding of how to draft claims. These are the legal meat of a patent, and must be written correctly in order to be enforcable. Remember that a patent simply gives you the right to exclude other people from using your idea; the legal term for their illegal use of your idea is "infringement". You must prove that they violated what you claimed about your invention in order to win a case; clearly, writing those claims requires both attention and skill.

- You may ultimately want or need a lawyer to work with you, and many of them will want to start from scratch using their preferred approach.

- If you want to file internationally, the workload increases dramatically, and an attorney's experience might be very welcome.